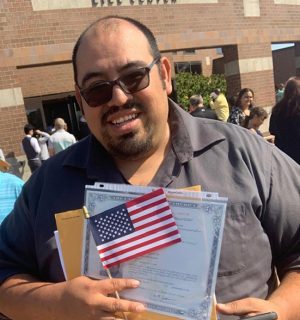

An Accomplishment 30+ Years in the Making

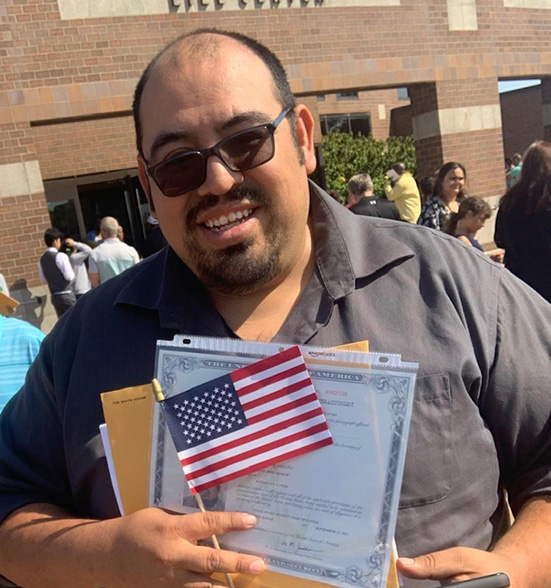

Juan Soto poses with his citizenship papers after being sworn in as an American citizen on Sept. 13, 2022. Juan’s path to citizenship began more than 30 years ago when he first moved to this country.

November 8, 2022

Juan Soto, a member of our Rockhurst staff, attained his U.S. citizenship on Sept. 13 after living here as a resident for more than 30 years. This important achievement is not only a huge milestone for him and his family, but it serves as a reminder to members of the Rockhurst community who don’t fully understand the struggles of immigrants in this country. Especially as we have just come out of Hispanic Heritage Month, students of color say it is crucial to have at least a baseline knowledge of our immigration system and see it through the eyes of people like Soto who have experienced it personally.

Originally from Colima, Mexico, Soto immigrated to the United States with his family at just seven years old. His father was working in California at the time, so his family made the decision to bring the rest of his family over and be reunited with his father. After entering the U.S., they, along with other Mexican nationals crossing the border, were surrounded and robbed by a local gang. That potentially traumatic event didn’t sway Soto’s family’s desire to be in America. They moved to northern Las Vegas and immediately submitted paperwork to attain their residency status. It took five years for them to attain paperwork.

Soto and his family lived in a predominantly Black neighborhood where he says that he was sometimes “discriminated [against] because [he] was Mexican” but “[he] knew that a lot of the Black kids that lived there also got picked on because of their color.” He has experienced firsthand people telling him “to ‘go back to [his] country.'”

Regardless of all the hardship Soto has endured, he maintained a determined outlook on his adopted home.

“This is nobody’s country…This country is free for everybody. You speak whatever language you want, there’s no set language for this country. Even if you’re born here…for having brown color skin or black color skin…you’re going to [hear things] all your life. Don’t listen to those words, don’t let it bother you…just continue your life.”

Soto spent the better part of three decades of his life trying to become a citizen. As he found out, it’s a complicated and sometimes frustrating process for all involved.

“The only thing harder than immigration law is the tax code, because it’s like a difficult puzzle with missing pieces that are nowhere to be found…It’s ambiguous, subjective and at times doesn’t make any sense,” said Ted Garcia Jr., an immigration attorney out of Kansas City, Kansas.

Most people try to get a legal permanent resident card, often called a “green card,” when they enter the country. This is usually acquired through a family member who is a lawful permanent resident or citizen that applies on their behalf. This process can take anywhere from two to 25 years, with a few exceptions.

Once you’ve acquired a green card, most people have to wait at least five years, be of “good moral character,” learn English, and pass civics, reading, and writing exams, explained Garcia. He says, in Kansas City, this process of obtaining citizenship takes 12 to 15 months, but varies across the country. This process is called naturalization.

There are a multitude of reasons people can be barred from obtaining citizenship, including crimes or immigration violations, like claiming to have been a citizen in the past for job-related reasons. Garcia said it is important to note that an immigration violation differs from a crime, and that often people violate immigration laws simply to gain employment.

Garcia said there exists very little symmetry in the U.S. immigration system, making it difficult for people to come here with hopes of escaping poverty or even when in danger. The majority of people who cross the border to the United States come here in search of a better life, and go on to be productive members of society that “disproportionately work in essential [jobs],” according to the US Joint Economic Committee.

Immigration is consistently a hot-button issue in political circles. But many of the dehumanizing stereotypes of immigrants created by both sides of the political spectrum become clearly untrue upon examining the real stories of people like Juan Soto, who now can take advantage of rights, such as voting, that many natural born citizens don’t think twice about.

“After living here all my life, and then going ahead and taking this test…It’s great…This is something bigger–sort of like graduating again,” said Soto.

![Head coach Billy Thomas gives instructions during the freshman portion of the first day of basketball tryouts on Oct. 30, 2023. After finishing second at districts last season, expectations are high in this year, Thomas third year. This year will be the culmination of [the first two years], because the players have fought injuries and they have bought into our culture. We’re looking forward to this year being the best year yet.](https://prepnewsonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/IMG_1436-edited-600x374.jpg)