Every day at Rockhurst, hundreds of students fill the bustling halls of the school. Each of these individuals has a unique story to tell. However, for seniors Mohamed (Hamid) Abdalla, Bahar (Baradin) Ahmed and Asende Welongo, life has been vastly different than their fellow Hawklets.

Throughout journeys that took them thousands of miles from where they began, the trio have encountered a lifetime full of challenges and exceptional moments. Ultimately, each of them represent a distinct perspective, forged by the dangerous, unpredictable, and irreplaceable adventures of their lives. Together, this trio forms an unbreakable bond that has changed the lives of students, families and the community of Rockhurst High School.

All three boys were born in different places in Africa between 2007 and 2008. All were affected by violence and economic hardship common across the continent. From their birth, all three experienced a turbulent upbringing.

In 2008, Ahmed was born in Sudan, a country ravaged by a seemingly endless flow of violence. Eight major military conflicts, including four civil wars, have ravaged these territories over the last 75 years. Resources, money, land, and lives have all been destroyed and lost throughout the chaos. Sudan’s political strife was a constant shadow over Ahmed’s young life. In one instance, his home was taken over by soldiers. His family fled the country when Ahmed was just a toddler.

“I moved when I was two years old to South Sudan because of the war. And then, from there, I went to Kenya,” Ahmed said.

Kenya is where Abdalla’s journey began.

“I was born in Kenya,” he said. “Growing up in Kenya, life was pretty hard… just not having the [resources]… to live, school wasn’t always the best… we [always had to]… work extra hard to… just support the family. Everybody’s just trying to find a job or just trying to live for themselves.”

Abdalla and his family fled to different places in Africa during his adolescence, including Sudan and, eventually, Tanzania.

Welongo’s upbringing was very different to Abdalla and Ahmed’s, even though he experienced similar day-to-day tribulations.

“I was born in Tanzania. My parents had fled from a war… in Congo,” he said. “I was there ‘till I was, like, nine years old.”

While Welongo, unlike Ahmed and Abdalla, never moved from his home country during his early years, he had his fair share of hardships.

“The hunger was… insane. Every day that… we went through we would have to figure out a way to get some food.”

Food insecurity in Africa has many causes. Frequent military conflict, as well as unreliable economic depression all factor into the region’s widespread food droughts.

“Just living day to day was… hard,” Abdalla said.

In many of these African countries, violence can be just around the corner.

“I think [in] Africa… you can get killed anytime,” Abdalla said. “Everybody’s just trying to survive.”

For the trio, education also reflected the challenges of everyday life. Oftentimes, children in Africa are crammed into small rooms and forced to use inadequate academic materials due to a lack of educational funding.

“When I was in Kenya, it was hard learning English… because… you’re in a class with over 70 people… and the teacher cannot help each [person] individually… So [I’d] been going to school in Kenya for five years, and I couldn’t even spell my name,” Ahmed said. “But then, when I came to the USA, I learned how to spell my name in the first two weeks.”

Priorities in Africa are often defined by everyday procedures. With many people focused on living day-to-day lives, education and planning for the future can be pushed aside.

“In Africa… most people… didn’t really have… dreams [of] what [they] could do because there’s not many things that [they] were capable of doing,” Welongo said. “[There] wasn’t much of that because [people] were all just planning… [to] work [or] make some money.”

Lack of education made the transition to the U.S. hard for the trio. In 2016, with their families, Abdalla and Ahmed immigrated to Kansas City from a Tanzania refugee camp. Welongo, on the other hand, immigrated to Erie, Pa. with most of his family. He still has a few siblings in Africa.

“The U.S. has always been a dream,” Abdalla said. “I think… even living in Africa… everybody was just talking about the U.S., how everybody wanted to come to the U.S.”

The new home was a culture shock for the boys. They experienced and saw things they had never imagined before. Welongo said it coming to America had an almost mystical quality to it.

“To be honest… I thought the U.S. was like heaven, because… it was like up in the sky… I didn’t know life outside of Tanzania or where I was… so… when we were flying, I… just saw a plane [and I thought] we [were] going to heaven.”

Even with its advantages, the U.S. still provided problems for Abdalla, Ahmed, and Welongo. In the unfamiliar territory, the main challenge the boys faced was the language barrier.

“I couldn’t understand anybody that was around me,” Ahmed said. “It felt like I was missing out. It felt like I wasn’t known. It felt like I was not associated with.”

Not being able to speak a language can cause many problems for refugees. In Welongo’s case, it manifested itself in repeated disrespect.

“[My sister and I] would have people throwing rocks at us and stuff on the way to school, and then at school it’d be a bunch of bullying that I… didn’t really understand,” he said. “And then later on, I came to understand that it’s probably because I was a different person. I didn’t speak their language. They didn’t understand me. They [didn’t] know who I was and so they thought it was fine to just do all… types of things [to me].”

The issues the three faced were not (and still aren’t) uncommon for many refugees and immigrants. Still, the U.S. provided a safe place where the boys could chase their dreams.

During their first years in the U.S., the trio continued to battle their way through the challenges of learning English. Watching television was a key way they learned the language.

In 2018, Welongo moved from Pennsylvania to Kansas City. This move eventually led to him meeting Ahmed and Abdalla through Global FC, a soccer team created for immigrants.

“When [I] went to Pennsylvania, that’s when I couldn’t play. I couldn’t… join [a team] or anything because they all [required money] and I couldn’t… afford any of that,” he said. “[In Kansas City, Global FC] was… the only free soccer team because all the other ones you had to pay to play… And so… I joined that team. [They] took care of me and… then I met… Mo and Bahar.”

In a completely new environment, soccer provided much needed continuity from the boys’ time in Africa.

In a completely new environment, soccer provided much needed continuity from the boys’ time in Africa.

“Whenever we [felt] like we [were] under stress… we could always lean on soccer,” Abdalla said.

The three have been connected to Rockhurst soccer all four of their years here. Welongo, in particular, has played varsity since he set foot on campus, playing an invaluable role in the team’s success. In 2024, he led the team in goals, and in 2023 and 2022, he played a key role in Rockhurst’s consecutive state championships.

The three’s soccer success is impressive considering the humble beginnings from which they came.

“I started playing when I was like three, four,” Ahmed said. “I got it from all my brothers… We would just wrap a bunch of socks together… or sometimes [we would] use plastic bags.”

“The only sport we knew, where I was born, was soccer. Nothing else,” Welongo said. “My brother was playing. My dad played. Everybody in… my household… played soccer.

“When I was like three years old [or] two years old, I started playing soccer. I used to play with my brothers… and… watch… games in the streets. There [was] a place that… had a TV, so everybody would gather up there if there [were] any games.”

The sport the boys had given so much to, always gave back to them. In times where they couldn’t speak English or the stress of being away from home bothered them, the boys always had soccer.

“Soccer isn’t just… about one person, it’s also about a whole. It’s about a group,” Abdalla said. “When [you’re] playing soccer, you’re connecting with each other… You’re creating new bonds.”

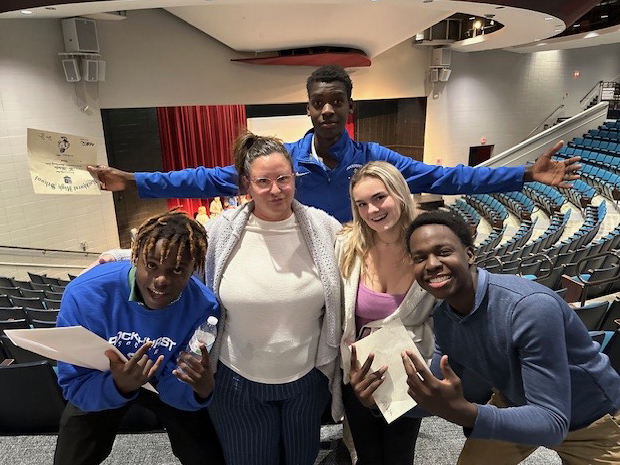

Two bonds the boys created were with Global FC coach Meghan Flavin and her daughter, Tierney. Through a combination of tutoring and coaching, the duo developed a strong connection with the three boys, eventually gaining legal guardianship of them.

“We met the boys when they were in seventh grade,” Meghan Flavin said. “I realized they had an acumen for more.”

Both Meghan and Tierney were vital in the development of the three boys. As the trio faced the language barrier of the United States, the mother-daughter duo helped them break it down during tutoring sessions.

“When it came to writing and reading and comprehension and things that you’re taught in second, [and] third grade, well, they didn’t have that, because they came here in third grade and didn’t speak English. So, it was hard for them,” Meghan Flavin said. “English is not their first language. They know four and five languages each.”

No story quite captures the divide the boys faced quite like Abdalla’s first time in the principal’s office. During his first few months of American education, Abdalla only knew one word. So when trouble came up at school and the teacher asked him if he caused the problem, naturally, he responded with what he knew.

“So, he said ‘Yes,’ and then he got sent to the principal’s office,” Tierney Flavin said, “because [it was] the only English word he knew.”

Eventually, with the help of the tutoring provided by the Flavins, the boys learned yet another language. But the help didn’t end there. The Flavins were instrumental in the boys’ acceptance into Rockhurst.

“In eighth grade, I signed them up to tour all the schools,” Meghan Flavin said. “They toured Rockhurst and Lincoln and… Bishop Miege… But… the day that I picked them up from their Rockhurst tour, all three of them were like, ‘That’s it. That’s where I’m going to go to high school.'”

With the boys set on going to such a prestigious school, Flavin knew they needed to embrace the challenge of getting admitted into Rockhurst.

“That’s the day that we started tutoring harder, meeting more often, you know, really getting into the nuts and bolts of what is it going to take to be a Rockhurst student?” she said.

When the boys did receive admission into Rockhurst, it was clear to Flavin that all the work and time invested was worth it.

“The day that I told them that they got accepted to Rockhurst… That’s one of my favorite memories… We drove to their houses and told them individually,” she said.

Now, more than three years into their Rockhurst experience, the brothers have embarked on their senior year.

“So far, my experience has been really great,” Abdalla said. “Coming here was one of the best decisions ever. I think getting the education from Rockhurst right here has also changed me in a lot of ways.”

The boys have enjoyed their time at Rockhurst, even though it has been something new for them. The trio mentioned that, during the early stages of their Rockhurst lives, they always knew upperclassmen had their back.

“When we were freshmen, a lot of the upperclassmen took care of us. Wherever we [went], they respected us… they presented us in a good way… and it means a lot,” Ahmed said. “So, you know, we’re just trying to pass that thing down to the coming generations.”

The trio continues today as an integral part of the student body, forging connections with all kinds of students. Their laid back and friendly demeanors cause fellow Hawklets to gravitate to them.

Overall, the experiences presented in this story are not shared to cast the three as victims. Instead, they’re intended to highlight strength of these young men. As a result of their struggles, the trio have gained a wise perspective on the world.

“A lot of kids, they take a lot of things for granted,” Abdalla said. “I say this because… a lot of kids just don’t understand what it’s like living outside the U.S. and what those people are going through.

“So, I think, here in the U.S., we just have a lot …here, we’re blessed. We’re blessed to have a good life… [we] just need to… be a little cautious and just be a little mindful… [that] not everybody [has] what we have.”

The trio’s contrasting experiences between the U.S. and Africa have given them a strong sense of gratitude, and the boys express it regularly.

“They’re so thankful for everything,” Meghan Flavin said. “They tell me all the time… that they wouldn’t be where they are… if it weren’t for T [Tierney] and I, and we continually tell them that they did this. They put the work in, you know. They deserve this opportunity.”

Another insight that surfaced during conversations with the boys was the belief in doing what one loves.

“My advice would be do what you want to do,” Welongo said. “Don’t let what others are doing control you or anything.”

Abdalla added to this point.

“Just go for it… You don’t have to be the best at something to try something… So, I think if you really want to try something, man, don’t even hesitate about it.”

Even though the experiences they have had are very personal to themselves, members of the Rockhurst community can learn numerous things from the lives of Abdalla, Ahmed, and Welongo. The boys’ openness about their journeys and differences from the lives of most students offers another perspective on how students, faculty and families can live fulfilling lives.

Additionally, through all of the instabilities they have faced in their lives, the boys have found a community they can count on here in Kansas City and at the Rock. Meghan Flavin sums it up:

“Family isn’t always what you’re born with. It’s what you make of it.”